The Priceless Lessons of a "Worthless" Album

Music has a funny way of showing its age. A doo-wop song with multiple vocalists singing into the same microphone? Definitely from the '50s. A pop song with a gated reverb on a drum machine's snare hit? Totally '80s. But what artifacts showcase the age of today's music? What gives away an album of the current decade? To answer this, we may just have to stop listening to the music altogether and turn our attention to something less noticed—something almost trivial. We may have to count the number of seconds in a song.

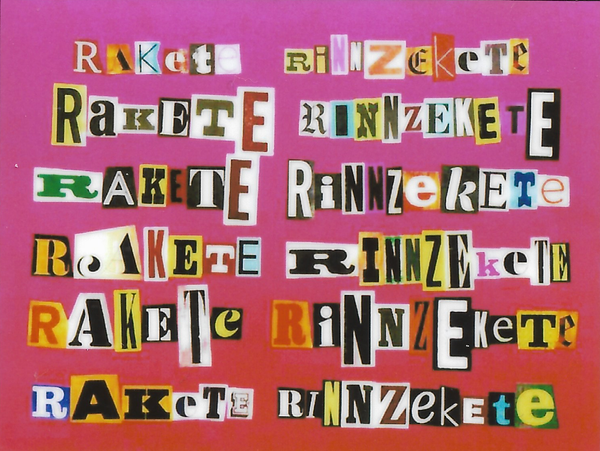

On July 29, 2021, Berlin-based electronic musician Valentin Hansen released "Crisis (The Worthless Album)," a debut LP containing a total of thirty 29-second songs. Now, you're probably asking yourself two questions: (1) why would someone ever refer to their own art as "worthless," and (2) why would someone ever make so many 29-second songs? The amusing part here—as you'll soon discover—is that each question answers the other.

For many streaming platforms (most notably Spotify, in Hansen's case), 30 seconds is the minimum threshold for (1) counting the number of times a song has been played, (2) counting the number of monthly listeners attributed to the artist, and (3) paying the artist from a streamed song. Despite how many people listen to Hansen's work and how much of it they consume, he has exactly zero streams, zero monthly listeners, and zero dollars of earned revenue.

But Hansen's output was more than music; it was a social commentary on how the commoditization and distribution of art often pervert, miscommunicate, and even devalue the art itself. Putting aside money and emotional appeal, the "value" of art has taken on a new meaning since the advent of social media. Internet clout has grown as a form of social currency which, although glorified by many, is often superficial and decidedly disposable (hence, interpretively worthless). Contrarily, the quiet but genuine appreciation of and admiration for Hansen's work by fans should be more valuable even though it does not equate to metrics or revenue. But does any of that matter if Spotify calculates it as "worthless?"

From Hansen's album, I take away three lessons about art, its resulting value, and our collective outlook on it: