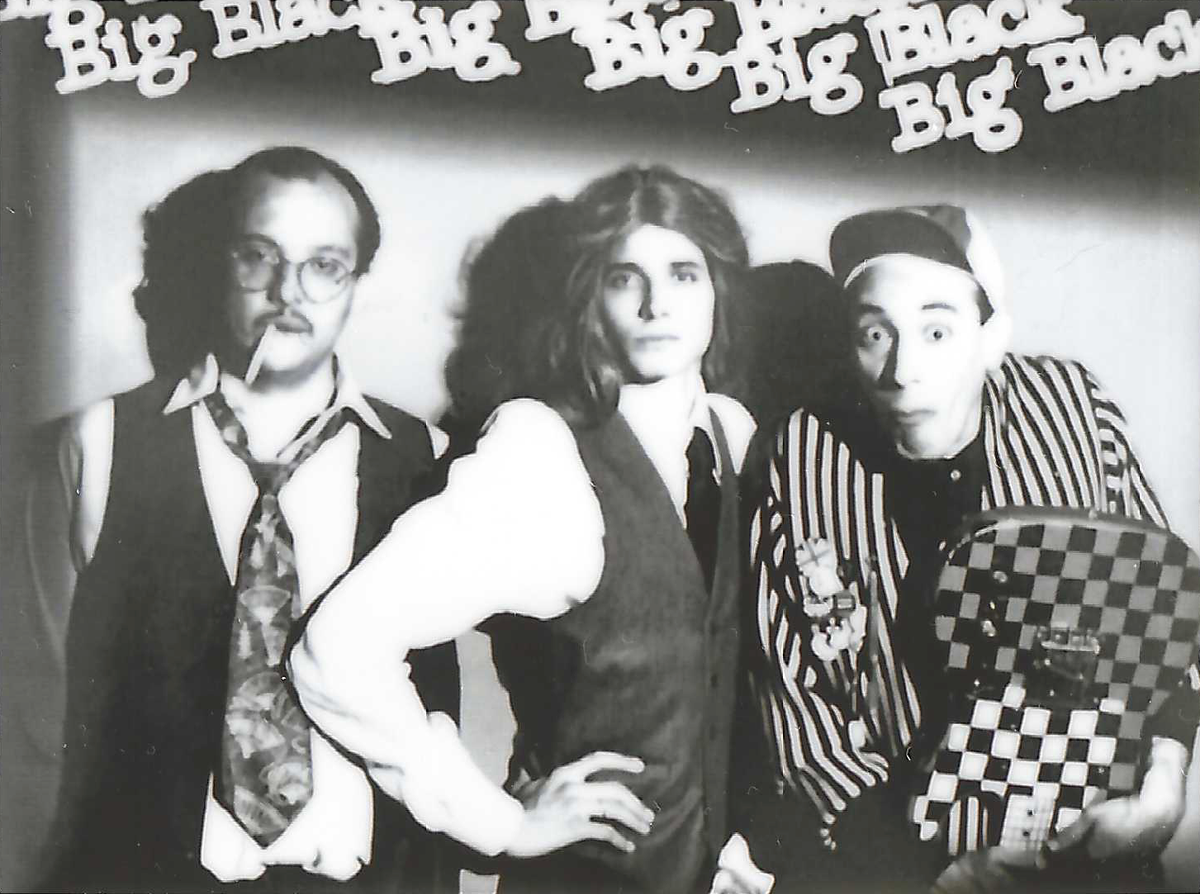

Three Lessons From Big Black: The Band That Stopped at Nothing to Talk About Everything

There are countless ways to describe Chicago-based proto-industrial group Big Black, but "shy" is not one of them. From 1981 until their split in 1987, they brought to light what was often swept under the mainstream rug. Among other topics, their songs discussed animal abuse, murder, misogyny, pedophilia, racism, corrupt politics, prostitution, and alcoholism. But amidst all of this, they weren't talking about themselves.

In this article, I will outline three lessons I learned from their approach to songwriting and what it means in the context of art.

In art, honesty holds greater weight than beauty.

One of Big Black's most startling songs, titled "Cables," shares how bored kids in Missoula, Montana would go to the slaughterhouse after school to watch the cattle die. (If you're brave enough to listen to this raw, grating song, note how the opening riff represents the noise of cables being pulled.) This is a classic case of living in a town where nothing interesting happens—where eventually, you have to make your own fun.

But that's what makes the song that much more impactful. Big Black's attitude regarding "Cables" was not of flowery imagery or quixotic notions, but of sobering immersion into the life of a high schooler with nothing better to do. To Montana-raised frontman Steve Albini, this was his world, his upbringing, his reality.

Distilling the judgment of art to the beauty it portrays ignores more meaningful characteristics, like truth, as a measurement of its impact. Ultimately, the more honest art is, the more weight it holds, the more it reflects the human condition, and, therefore, the more we can embrace it as a tool to understand ourselves better.

Separating the art from the artist works both ways.

The expression "separating the art from the artist" exclusively serves to intellectually distance the perceived immorality of an artist's behavior and/or beliefs from the appreciation of their work. But what if it was the work that appeared immoral, not the artist?

Big Black challenged their audience by adopting this exact premise, vocalizing various qualms and predicaments for listeners to confront directly. Despite this taking place under the creative license of art, controversy ensued.

Perhaps listeners don't consume music like they do horror novels and slasher films, but this inability to interpret music like such is a fault. Ultimately, art is art, which in itself should release artists from being conflated with their work's subject matter. (For instance, an art piece focusing on violence should not suggest that the artist is violent.)

The next logical extension of this is whether the artist is promoting or endorsing a subject by referencing it in their art, which leads me to the next lesson.

Art does not inherently communicate advocacy.

Trite as it is, the first step in solving a problem is recognizing that there is one. Big Black applied a "sunlight is a great disinfectant" approach here, bringing to light social issues and injustices that were often snuffed by or misrepresented in commercial media. Far more effective than outright accosting a position was satirically endorsing it to invite objection, which upon receiving it proved the position to be both objectionable and worthy of more discussion. Perhaps the most famous example of this rhetorical approach was Jonathan Swift's 18th-century book A Modest Proposal (which suggested eating children to resolve Ireland's poverty). Unfortunately, this method has been lost to more literal measures taken in media, perhaps for fear of being misunderstood or cancelled.

But Big Black knew better—they understood the efficacy of ironic endorsement. By upstanding an immoral argument (or even suggesting their moral belief in it, per mention of it via their music), they could educate those unfamiliar with a particular event, spark debate, and provide an opportunity for listeners to bind together against a common cause. Want an example? Look no further than the liner notes of their song "Pigeon Kill":

"In Huntington, Indiana, there is an annual event, the pigeon kill, during which the townspeople feed strychnine-laced corn to the town's pigeons. Sometimes the children are given the responsibility of feeding the pigeons. They think of it as play."

(The KEXP library copy of their "The Hammer Party" compilation includes a news clipping, sharing more insight on the event.)

Knowing that art does not inherently communicate advocacy should be obvious, but time and time again, art is misinterpreted by being ingested literally and as a reflection of the artist's own stance(s). Even putting aside the roles of escapism and catharsis in art, Big Black's adamancy to reject literalism serves as a lesson for artists looking to enlighten their audiences and vocalize their beliefs in a manner that ignites a stronger reaction and leaves a lasting impression.

Big Black affected not only what music I listen to but (perhaps more importantly) how I listen to music as well. I hope that, with these lessons in mind, listeners can expand their tastes to consume and appreciate art that they might otherwise quickly or—worse—wrongfully dismiss. 👊